Murphy's law

Murphy's law[a] is an adage or epigram that is typically stated as: "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.".

Though similar statements and concepts have been made over the course of history, the law itself was coined by, and named after, American aerospace engineer Edward A. Murphy Jr.; its exact origins are debated, but it is generally agreed it originated from Murphy and his team following a mishap during rocket sled tests some time between 1948 and 1949, and was finalized and first popularized by testing project head John Stapp during a later press conference. Murphy's original quote was the precautionary design advice that "If there are two or more ways to do something and one of those results in a catastrophe, then someone will do it that way."[1][2]

The law entered wider public knowledge in the late 1970s with the publication of Arthur Bloch's 1977 book Murphy's Law, and Other Reasons Why Things Go WRONG, which included other variations and corollaries of the law. Since then, Murphy's law has remained a popular (and occasionally misused) adage, though its accuracy has been disputed by academics.

Similar "laws" include Sod's law, Finagle's law, and Yhprum's law, among others.

History

[edit]

The perceived perversity of the universe has long been a subject of comment, and precursors to the modern version of Murphy's law are abundant. According to Robert A. J. Matthews in a 1997 article in Scientific American,[3] the name "Murphy's law" originated in 1949, but the concept itself had already long since been known. As quoted by Richard Rhodes,[4]: 187 Matthews said, "The familiar version of Murphy's law is not quite 50 years old, but the essential idea behind it has been around for centuries. […] The modern version of Murphy's Law has its roots in U.S. Air Force studies performed in 1949 on the effects of rapid deceleration on pilots." Matthews goes on to explain how Edward A. Murphy Jr. was the eponym, but only because his original thought was modified subsequently into the now established form that is not exactly what he himself had said. Research into the origin of Murphy's law has been conducted by members of the American Dialect Society (ADS).

Mathematician Augustus De Morgan wrote on June 23, 1866:[5] "The first experiment already illustrates a truth of the theory, well confirmed by practice, what-ever can happen will happen if we make trials enough." In later publications "whatever can happen will happen" occasionally is termed "Murphy's law", which raises the possibility that "Murphy" is simply "De Morgan" misremembered.[6]

ADS member Stephen Goranson found a version of the law, not yet generalized or bearing that name, in a report by Alfred Holt at an 1877 meeting of an engineering society.

It is found that anything that can go wrong at sea generally does go wrong sooner or later, so it is not to be wondered that owners prefer the safe to the scientific … Sufficient stress can hardly be laid on the advantages of simplicity. The human factor cannot be safely neglected in planning machinery. If attention is to be obtained, the engine must be such that the engineer will be disposed to attend to it.[7]

ADS member Bill Mullins found a slightly broader version of the aphorism in reference to stage magic. The British stage magician Nevil Maskelyne wrote in 1908:

It is an experience common to all men to find that, on any special occasion, such as the production of a magical effect for the first time in public, everything that can go wrong will go wrong. Whether we must attribute this to the malignity of matter or to the total depravity of inanimate things, whether the exciting cause is hurry, worry, or what not, the fact remains.[8]

In astronomy, "Spode's Law" refers to the phenomenon that the skies are always cloudy at the wrong moment; the law was popularized by amateur astronomer Patrick Moore[9] but dates from the 1930s.[10]

In 1948, humorist Paul Jennings coined the term resistentialism, a jocular play on resistance and existentialism, to describe "seemingly spiteful behavior manifested by inanimate objects",[11] where objects that cause problems (like lost keys or a runaway bouncy ball) are said to exhibit a high degree of malice toward humans.[12][13]

In 1952, as an epigraph to the mountaineering book The Butcher: The Ascent of Yerupaja, John Sack described the same principle, "Anything that can possibly go wrong, does", as an "ancient mountaineering adage".[14]

Association with Murphy

[edit]

Differing recollections years later by various participants make it impossible to pinpoint who first coined the saying Murphy's law. The law's name supposedly stems from an attempt to use new measurement devices developed by Edward A. Murphy, a United States Air Force (USAF) captain and aeronautical engineer.[15] The phrase was coined in an adverse reaction to something Murphy said when his devices failed to perform and was eventually cast into its present form prior to a press conference some months later – the first ever (of many) given by John Stapp, a USAF colonel and flight surgeon in the 1950s.[15][16]

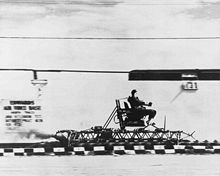

From 1948 to 1949, Stapp headed research project MX981 at Muroc Army Air Field (later renamed Edwards Air Force Base)[17] for the purpose of testing the human tolerance for g-forces during rapid deceleration. The tests used a rocket sled mounted on a railroad track with a series of hydraulic brakes at the end. Initial tests used a humanoid crash test dummy strapped to a seat on the sled, but subsequent tests were performed by Stapp, at that time a USAF captain. During the tests, questions were raised about the accuracy of the instrumentation used to measure the g-forces Captain Stapp was experiencing. Edward Murphy proposed using electronic strain gauges attached to the restraining clamps of Stapp's harness to measure the force exerted on them by his rapid deceleration. Murphy was engaged in supporting similar research using high speed centrifuges to generate g-forces.

During a trial run of this method using a chimpanzee, supposedly around June 1949, Murphy's assistant wired the harness and the rocket sled was launched. The sensors provided a zero reading; however, it became apparent that they had been installed incorrectly, with some sensors wired backwards. It was at this point a frustrated Murphy made his pronouncement, despite being offered the time and chance to calibrate and test the sensor installation prior to the test proper, which he declined somewhat irritably, getting off on the wrong foot with the MX981 team. George E. Nichols, an engineer and quality assurance manager with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was present at the time, recalled in an interview that Murphy blamed the failure on his assistant after the failed test, saying, "If that guy has any way of making a mistake, he will."[15][unreliable source?] Nichols' account is that "Murphy's law" came about through conversation among the other members of the team; it was condensed to "If it can happen, it will happen", and named for Murphy in mockery of what Nichols perceived as arrogance on Murphy's part. Others, including Edward Murphy's surviving son Robert Murphy, deny Nichols' account,[15][unreliable source?] and claim that the phrase did originate with Edward Murphy. According to Robert Murphy's account, his father's statement was along the lines of "If there's more than one way to do a job, and one of those ways will result in disaster, then he will do it that way."

The phrase first received public attention during a press conference in which Stapp was asked how it was that nobody had been severely injured during the rocket sled tests. Stapp replied that it was because they always took Murphy's law under consideration; he then summarized the law and said that in general, it meant that it was important to consider all the possibilities (possible things that could go wrong) before doing a test and act to counter them. Thus Stapp's usage and Murphy's alleged usage are very different in outlook and attitude. One is sour, the other an affirmation of the predictable being surmountable, usually by sufficient planning and redundancy. Nichols believes Murphy was unwilling to take the responsibility for the device's initial failure (by itself a blip of no large significance) and is to be doubly damned for not allowing the MX981 team time to validate the sensor's operability and for trying to blame an underling in the embarrassing aftermath.

The name "Murphy's law" was not immediately secure. A story by Lee Correy in the February 1955 issue of Astounding Science Fiction referred to "Reilly's law", which states that "in any scientific or engineering endeavor, anything that can go wrong will go wrong".[18] Atomic Energy Commission Chairman Lewis Strauss was quoted in the Chicago Daily Tribune on February 12, 1955, saying "I hope it will be known as Strauss' law. It could be stated about like this: If anything bad can happen, it probably will."[19]

Arthur Bloch, in the first volume (1977) of his Murphy's Law, and Other Reasons Why Things Go WRONG series, prints a letter that he received from Nichols, who recalled an event that occurred in 1949 at Edwards Air Force Base that, according to him, is the origination of Murphy's law, and first publicly recounted by Stapp. An excerpt from the letter reads:

The law's namesake was Capt. Ed Murphy, a development engineer from Wright Field Aircraft Lab. Frustration with a strap transducer which was malfunctioning due to an error in wiring the strain gage bridges caused him to remark – "If there is any way to do it wrong, he will" – referring to the technician who had wired the bridges at the Lab. I assigned Murphy's law to the statement and the associated variations.[20]

Disputed origins

[edit]The association with the Muroc incident is by no means secure. Despite extensive research, no trace of documentation of the saying as "Murphy's law" has been found before 1951. The next citations are not found until 1955, when the May–June issue of Aviation Mechanics Bulletin included the line "Murphy's law: If an aircraft part can be installed incorrectly, someone will install it that way",[21] and Lloyd Mallan's book Men, Rockets and Space Rats, referred to: "Colonel Stapp's favorite takeoff on sober scientific laws—Murphy's law, Stapp calls it—'Everything that can possibly go wrong will go wrong'." In 1962, the Mercury Seven attributed Murphy's law to United States Navy training films.[21]

Fred R. Shapiro, the editor of the Yale Book of Quotations, has shown that in 1952 the adage was called "Murphy's law" in a book by Anne Roe, quoting an unnamed physicist:

he described [it] as "Murphy's law or the fourth law of thermodynamics" (actually there were only three last I heard) which states: "If anything can go wrong, it will."[22]

In May 1951, Anne Roe gave a transcript of an interview (part of a thematic apperception test, asking impressions on a drawing) with said physicist: "As for himself he realized that this was the inexorable working of the second law of the thermodynamics which stated Murphy's law 'If anything can go wrong it will'. I always liked 'Murphy's law'. I was told that by an architect."[23] ADS member Stephen Goranson, investigating this in 2008 and 2009, found that Anne Roe's papers, held in the American Philosophical Society's archives in Philadelphia, identified the interviewed physicist as Howard Percy "Bob" Robertson (1903–1961). Robertson's papers at the Caltech archives include a letter in which Robertson offers Roe an interview within the first three months of 1949, making this apparently predate the Muroc incident said to have occurred in or after June 1949.[15][unreliable source?]

John Paul Stapp, Edward A. Murphy, Jr., and George Nichols were jointly awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2003 in engineering " for (probably) giving birth to the name".[24] Murphy's Law was also the theme of 2024 Ig Nobel Prize ceremony.[25]

Academic and scientific views

[edit]According to Richard Dawkins, so-called laws like Murphy's law and Sod's law are nonsense because they require inanimate objects to have desires of their own, or else to react according to one's own desires. Dawkins points out that a certain class of events may occur all the time, but are only noticed when they become a nuisance. He gives an example of aircraft noise pollution interfering with filming: there are always aircraft in the sky at any given time, but they are only taken note of when they cause a problem. This is a form of confirmation bias, whereby the investigator seeks out evidence to confirm their already-formed ideas, but does not look for evidence that contradicts them.[26]

Similarly, David Hand, emeritus professor of mathematics and senior research investigator at Imperial College London, points out that the law of truly large numbers should lead one to expect the kind of events predicted by Murphy's law to occur occasionally. Selection bias will ensure that those ones are remembered and the many times Murphy's law was not true are forgotten.[27]

There have been persistent references to Murphy's law associating it with the laws of thermodynamics from early on (see the quotation from Anne Roe's book above).[22] In particular, Murphy's law is often cited as a form of the second law of thermodynamics (the law of entropy) because both are predicting a tendency to a more disorganized state.[28] Atanu Chatterjee investigated this idea by formally stating Murphy's law in mathematical terms and found that Murphy's law so stated could be disproved using the principle of least action.[29]

Variations (corollaries) of the law

[edit]From its initial public announcement, Murphy's law quickly spread to various technical cultures connected to aerospace engineering.[30] Before long, variations of the law applied to different topics and subjects had passed into the public imagination, changing over time. Arthur Bloch compiled a number of books of corollaries to Murphy's law and variations thereof, the first being Murphy's Law, and Other Reasons Why Things Go WRONG, which received several follow-ups and reprints.[20]

Yhprum's law is an optimistic reversal of Murphy's law, stating that "anything that can go right will go right". Its name directly references this, being "Murphy" in reverse.

Management consultant Peter Drucker formulated "Drucker's law" in dealing with complexity of management: "If one thing goes wrong, everything else will, and at the same time."[31]

"Mrs. Murphy's law" is a corollary of Murphy's law, which states that "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong while Mr. Murphy is out of town."[32][33][34][35]

The term is sometimes used to describe concise, ironic, humorous rules of thumb that often do not share a relation to the original law or Edward Murphy himself, but still posit him as a relevant expert in the law's subject. Examples of these "Murphy's laws" include those for military tactics, technology, romance, social relations, research, and business.[36][37][38]

See also

[edit]- Buttered toast phenomenon – Idiom representing pessimistic outlooks

- Defensive design – Practice of planning for contingencies in the design stage of a project

- Finagle's law – Adage

- Hanlon's razor – Adage to assume stupidity over malice

- Hindsight bias – Type of confirmation bias

- Hofstadter's law – Self-referential adage referring to time estimates

- Totalitarian principle – Quantum mechanics principle stating: "Everything not forbidden is compulsory"

- Infinite monkey theorem – Counterintuitive result in probability

- Jinx – Curse attracting bad luck in superstition and folklore

- Laws of infernal dynamics – Adage about the cursedness of the universe

- List of eponymous laws – Adages and sayings named after a person

- Milo Murphy's Law – American animated TV series (2016-2019)

- Muphry's law – Adage related to Murphy's Law

- Parkinson's law – Adage that work expands to fill its available time

- Pessimism – Negative mental attitude

- Precautionary principle – Risk management strategy

- Segal's law – Adage about conflicting sources of information

- Shit happens – Slang phrase used as a simple existential observation

- SNAFU

- Sod's law – British culture axiom

- Unintended consequences – Unforeseen outcomes of an action

- Worst-case scenario – Concept in risk management to consider the most severe outcome that can reasonably be projected

- Yhprum's Law – The opposite of Murphy's law, stating anything that can go right will go right

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also less commonly known as Stapp's law and the fourth law of thermodynamics, and historically as Reilly's law.

References

[edit]- ^ "Edward A. Murphy, Jr. Quotes - 2 Science Quotes - Dictionary of Science Quotations and Scientist Quotes". todayinsci.com. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Dr Karl - Murphy's Law". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Matthews, Robert A.J. (April 1997). "The Science of Murphy's Law". Scientific American. 276 (4): 88–91. Bibcode:1997SciAm.276d..88M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0497-88.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (1999). Visions of technology: a century of vital debate about machines, systems, and the human world. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684839035.

- ^ "Supplement to the Budget of Paradoxes", The Athenaeum no. 2017 p. 836 col. 2 [and later reprints: e.g. 1872, 1915, 1956, 2000]

- ^ "LISTSERV 16.0". Linguist List. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ "Holt, Alfred. 'Review of the Progress of Steam Shipping during the last Quarter of a Century', Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Vol. LI, Session 1877–78 – Part I, at 2, 8 (November 13, 1877 session, published 1878)". Listserv.linguistlist.org. 2007-10-10. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ "Maskelyne, Nevil. 'The Art In Magic', The Magic Circular, June 1908, p. 25". Linguist List. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Patrick Moore (1957). The Amateur Astronomer. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35, 74.

- ^ Eric Partridge (1984). Paul Beale (ed.). A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. p. 1129.

- ^ Paul Hellwig, Insomniac's Dictionary (Ivy Books, 1989)

- ^ "Report on Resistentialism", The Spectator, 23 April 1948

- ^ "Thingness of Things", The New York Times, 13 June 1948

- ^ Sack, John. The Butcher: The Ascent of Yerupaja epigraph (1952), reprinted in Shapiro, Fred R., ed., The Yale Book of Quotations 529 (2006).

- ^ a b c d e Spark, Nick T. (2013). A History of Murphy's Law. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935700-79-1.

- ^ The Fastest Man on Earth Archived 2009-10-14 at the Wayback Machine – Improbable Research

- ^ Rogers Dry Lake – National Historic Landmark at National Park Service

- ^ "Astounding Science-Fiction, February 1955, p. 54". Linguist List. Archived from the original on 2008-06-21. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ "Chicago Daily Tribune, February 12, 1955, p. 5". Linguist List. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ a b Bloch, Arthur (1980 edition). Murphy's Law, and Other Reasons Why Things Go WRONG, Los Angeles: Price/Stern/Sloan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-8431-0428-7, pp. 4–5

- ^ a b Shapiro, Fred R., ed., The Yale Book of Quotations 529 (2006).

- ^ a b "Roe, Anne, The Making of a Scientist 46–47 (1952, 1953)". Linguist List. Archived from the original on 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Genetic Psychology Monographs volume 43, p. 204

- ^ "Past Ig Winners". improbable.com. 2006-08-01. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- ^ "The 34th First Annual Ig Nobel Ceremony". improbable.com. 2024-07-07. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- ^ Dawkins, pp. 220-222

- ^ Hand, pp. 197-198

- ^ Robert D. Handscombe, Eann A. Patterson, The Entropy Vector: Connecting Science and Business, p134, World Scientific, 2004, ISBN 981-238-571-1.

- ^ Chatterjee, p. 1

- ^ "Murphy's Law". Jargon File. Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Drucker, Peter F. Management, Tasks, Responsibilities, and Practices, p. 681

- ^ Arthur Bloch (1998), Murphy's Law 2000, p. 4

- ^ William H. Shore (1994), Mysteries of life and the universe, p. 171

- ^ Harold Faber (1979), The Book of laws, p. 110

- ^ Ann Landers (May 9, 1978), "Mrs. Murphy's Law", The Washington Post

- ^ "Cheap Thoughts". www.angelo.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Murphy's laws". www.cs.cmu.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Murphy's Laws of Combat Operations". meyerweb.com. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nick T. Spark (2006). A History of Murphy's Law. Periscope Film. ISBN 978-0-9786388-9-4.

- Paul Dickson (1981). "Murphy's law". The Official Rules. Arrow Books. pp. 128–137. ISBN 978-0-09-926490-3.

- Klipstein, D. L. (August 1967). "The Contributions of Edsel Murphy to the Understanding of the Behaviour of Inanimate Objects". EEE Magazine. 15.

- Matthews, R A J (1995). "Tumbling toast, Murphy's Law and the Fundamental Constants". European Journal of Physics. 16 (4): 172–176. Bibcode:1995EJPh...16..172M. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/16/4/005. S2CID 250909096.

Why toasted bread lands buttered-side-down.

- Matthews received the Ig Nobel Prize for physics in 1996 for this work (see list).

- Chatterjee, Atanu (2016). "Is the statement of Murphy's Law valid?". Complexity. 21 (6): 374–380. arXiv:1508.07291. Bibcode:2016Cmplx..21f.374C. doi:10.1002/cplx.21697. S2CID 27224613.

Is the statement of Murphy's Law valid?

- David J. Hand ( 2014). The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences, Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day, Macmillan, ISBN 0374711399.

- Richard Dawkins (2012). The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really True, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 1451690134.

External links

[edit]- 1952 proverb citation

- 1955 term citation of phrase "Murphy's law"

- Murphy's law entry in the Jargon File

- Murphy's Law of Combat

- Murphy's Law's Origin Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Reference to 1941 citation of the proverb

- The Annals of Improbable Research tracks down the origins of Murphy's law